As cars get more fuel-efficient and as more hybrids and electric vehicles become available, drivers will be spending less money at the pump.

As cars get more fuel-efficient and as more hybrids and electric vehicles become available, drivers will be spending less money at the pump.

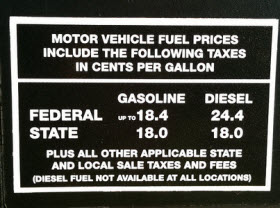

For states, that means a drop in gas-tax revenue, which goes to fund road construction, repair and other car-centric infrastructure. With the federal government’s push for higher fuel efficiency via CAFE regulations that propose passenger vehicles achieve an adjusted fleet average of 54.5 mpg by 2025, the gas-tax cash crunch will only get worse.

That’s why more states are considering a “vehicle miles traveled” tax to make up for gas-tax revenue shortfalls. The logic is that under the current gas-tax system, drivers in highly fuel-efficient vehicles pay much less than vehicles that aren't as fuel efficient – an EV driver can effectively pay nothing – even though they use the same roads. A VMT tax is seen as more equitable since it’s based on actual road use instead of fuel burned.

But implementing a VMT tax involves hurdles ranging from mileage verification to privacy issues. That’s why VMT advocates will be closely watching a pilot program in Oregon scheduled to kick off in 2015 that includes 5,000 volunteer drivers and is designed to prove to the public and reluctant lawmakers that a VMT tax can work.

Lawmakers also hope to prove that the mileage-tracking technology won't be used by the government to keep tabs on you.

USA Today ran a comprehensive story last week on the details of the Oregon program. But we had a chance to talk with the author of the Oregon bill, state Rep. Vicki Berger of Salem, the ranking Republican on the House Revenue Committee, to get her thoughts on why she’s pushing for a VMT tax in the state and her experience with her own mileage being tracked.

Berger said she believes that since vehicles are only going to get more fuel-efficient, her bill and advocacy for a VMT tax are an attempt to get in front of the problem of dropping gas-tax revenues.

“I worry that if you wait very long, you’ll have a bunch of these highly fuel-efficient vehicles on the road,” she told MSN Autos. “And you’ll either have to grandfather them in or you surprise people: 'I bought this car to save money on gas and now you’re taxing me?’

"I don’t like either of those scenarios,” she said. “And the fact is, if you pay for your roads through gas taxes and you have a significant group of people who aren’t paying it, you have a problem.”

"The amount of revenue 'lost' is tough to calculate," Jaime Rall, a senior policy specialist at the National Conference of State Legislatures, told MSN Autos in an email. "There are many variables, including state gas-tax rates, how many fuel-efficient vehicles are being driven in each state, how much they’re being driven, what vehicles they’re replacing and so on."

At least eight states have tried to introduce VMT legislation this year. In total, 18 states have tried VMT pilot programs but none as comprehensive as in Oregon, Rall said. "There's no question about it: States want to know if this is going to be a viable way to fund transportation into the future," she said.

Berger noted that the pilot program includes a variety of vehicles to get a sense of how a VMT tax would affect various car owners. “What we’re trying to see is how this would work with an electric vehicle, with a Toyota Prius or other hybrid, with a standard gas-powered sedan or a pickup truck,” she said. “At the end of the study, we’ll have very good data on how this would work with different vehicles.”

Berger took part in a smaller pilot program last year driving her own Volvo. She acknowledged that some participants, as well as some lawmakers, are wary of having state-installed GPS tracking devices in private vehicles as part of the program.

For the upcoming VMT pilot, Oregon will use private companies to provide two different mileage-tracking technologies: basic meters that use a vehicle's odometer to log miles driven and more advanced meters that use GPS to track where cars travel and how far. Oregon officials also hope to develop a smartphone application to augment the basic meters.

USA Today noted that Berger's bill limits who can access the mileage information and stipulates that the state and its affiliates have to destroy any location information within 30 days after using it for billing. It added that Oregon and other states already use mileage meters to track trucks and tax them by the number of miles driven and based on their weight. And some drivers now allow insurance companies to track their driving in exchange for a discount.

“It’s pretty clear to me that this technology is here,” Berger said. While some people will be concerned about privacy, "you can track miles without tracking where you go. It’s not that complicated."

Berger said that while we don’t know “what’s coming in terms of [fuel-efficiency] technology, we do know that gas mileage is getting better and better. And what that means for highway construction and repair is that the funding is getting smaller and smaller.”

Doug Newcomb has been covering car technology for more than 20 years for outlets ranging from Rolling Stone to Edmunds.com. In 2008, he published his first book, "Car Audio for Dummies" (Wiley). He lives and drives in Hood River, Ore., with his wife and two kids, who share his passion for cars and car technology, especially driving and listening to music.

Source: MSN

No comments:

Post a Comment